Venture Capital Funds Formation Guide

Contact our team to discuss the process of launching your venture capital fund. Email: info@dilendorf.com. Phone: 212.457.9797.

Dilendorf Law Team prepared this summary for venture capital (“VC”) funds and describes the compliance implications under the US federal and state securities laws.

We assist emerging and established investment managers with forming traditional and tokenized VC funds for FinTech, PropTech, Biotech, Web3, Healthcare and Eot industries.

Our clients are advisers to VC funds, and we regularly counsel clients with respect to the formation and offering of interests in traditional and tokenized VC funds they advise.

This summary is intended to help emerging and established fund managers understand securities laws considerations and exemptions when designing a venture capital fund structure.

It’s not intended to be a comprehensive description of all federal and state securities laws and rules that may apply to transactions conducted with offers, sales and issuance of traditional or tokenized VC fund securities.

Whether certain VC fund activities require registration of the offering of securities, broker-dealer registration, investment company registration, or investment adviser registration is a fact-specific analysis that must be conducted on a case-by-case basis.

Specifically, this summary discusses:

- What are private (traditional + tokenized) venture capital funds;

- Timeline for launching a venture capital fund;

- Fees for launching a VC fund and reimbursement of formation fees to a fund manager;

- When interests in VC funds would be “securities” under federal and state securities laws;

- Registration of securities offerings with the SEC and/or state securities regulators and potential exemptions from securities registration for investments in a VC fund (particularly through Rule 506 of the Federal Regulation D);

- Restrictions under state law applicable to Rule 506 VC fund offerings;

- Registration and exemptions from registration for a VC fund are “investment companies” and considerations for advisers to a real estate fund;

- Keys terms of a venture capital fund;

- Onshore v. offshore funds;

- Issuance of tokenized fund shares.

1.What are privte (traditional and tokenized) venture capital funds?

A fund is an entity created to pool money from multiple investors—often referred to as limited partners. Each investor makes an investment in the fund by purchasing an interest in the fund entity, and the adviser uses that money to make investments on behalf of the fund.

Traditional venture funds typically invest in businesses in exchange for equity and some firms specialize in particular industries or in companies at a certain stage (for example, early, mature, or later stage).

In a tokenized fund, a fund manager could create blockchain tokens representing investors’ ownership interest in a fund.

The benefit of tokenization is that all operations like token issuance, investor subscription, preferred return distributions, and secondary market trading are managed via blockchain smart contracts without any physical paperwork.

These tokens would be treated as securities in the US, and so all regulatory requirements, including jurisdictional restrictions, KYC/AML, are automatically enforced via smart contracts.

Chief among the advantages of tokenization is liquidity. Currently, limited partnership interests in private (traditional) funds are considered relatively illiquid. Tokenized fund interests (security tokens) could be on regulated security token markets aks alternative trading systems (ATS) in complied with federal and state securities regulations.

2. How long does it take to launch venture capital fund?

The average timeline for structuring and launching a venture capital fund offering exempt from registration with the Securities and Exchange Commission is 3-5 weeks.

It could take 6-8 weeks to launch an exempt tokenized VC fund, shares of which can be traded on regulated security token marketplaces also known as alternative trading systems operated using blockchain technologies.

3.How much does it cost to launch a VC fund and reimbursement of formations fees to a fund manager?

The fees (legal, registration, tax) for launching a stand-alone a VC fund could range between $35,000 to $60,000. Ongoing annual fund administration fees could vary between $15,000 – $50,000 depending on the fund’s complexity, size of the fund and numbers of investors. The fees for launching a tokenized VC fund could be as high as $100,000.

The fund reimburses the fund managers all actual costs and expenses incurred in connection with the formation, organization, legal and marketing of the fund. The fund can amortize such costs over a three or five years and reimburse the general partner for advancing costs and fees on behalf of the fund.

4. Are interests in a venture capital funds“Securities”?

All offers, sales, and issuance of securities are governed by federal securities rules and regulations.

Under federal and state laws, securities are defined broadly to include shares of limited partnership interests and membership interests in an LLC, LLP and investment contracts.

Interests in a private venture capital fund offered and sold to investors will typically constitute securities within the meaning of federal and state laws.

As a result, VC funds must comply with all applicable regulations of the Securities and Exchange Commission (“SEC”) and the securities regulators in the states where a VC fund operates. This includes being aware of, and complying with, applicable provisions such as the registration and anti-fraud provisions of federal and state securities laws.

5. Are VC fund offerings required to be registered with the SEC Commission and the states, or are exemptions from registration available?

Under the federal Securities Act of 1933 (Securities Act), all offers and sales of securities must be either (1) registered with the SEC or (2) conducted in compliance with an exemption from registration. State securities laws also require registration or an exemption from registration before securities may be offered or sold in the state.

Securities regulators interpret broadly the meaning of the term “offer.” For example, advertising a business opportunity could be considered an offer; therefore, it is prudent to assume that efforts to attract investors to a VC fund are offers of a security and subject to federal and state securities laws.

The good news is that offerings of private VC fund interests may not need to be registered with the SEC or state securities regulators if an exemption from registration is available.

Federal and state securities laws contain several exemptions from registration that fund managers could rely on when launching a venture capital fund. For example, some frequently used exemptions from registration that may be available to VC fund sponsors include:

- Rule 506(b) of Regulation D, which provides an exemption from registration for a private offering to accredited investors and up to 35 sophisticated investors; and

- Rule 506(c) of Regulation D, which provides an exemption from registration for an offering that may be conducted publicly so long as the VC fund takes reasonable steps to verify the accredited investor status of each purchaser.

6. Are there any restrictions under state law applicable to Rule 506 venture capital fund offerings?

Although federal law preempts state registration and qualification under Rule 506, the states have the authority to require notice filings and collect state fees in connection with VC fund offerings.

In almost every state, a VC fund sponsor making a Rule 506(b) or Rule 506(c) offering could be required to submit a notice to state regulators within 15 days of the first sale to an in-state investor.

Issuers should contact state securities regulators in the states in which they intend to offer or sell securities for further information on state requirement

7. Is the venture capital fund required to register an “Investment Company”?

VC funds can also implicate the registration provisions of the Investment Company Act of 1940 (Investment Company Act) and, potentially, the Investment Advisers Act of 1940 (Advisers Act) or related provisions of state securities laws.

However, there are exception to the Investment Company registration rules. Below are some high-level summaries of exclusions from the definition of “investment company” under the Investment Company Act that might apply:

Private Fund Exclusions – Section 3(c)(1) and Section 3(c)(7)

Section 3(c)(1) of the Investment Company Act states, in part, that an issuer is not an investment company if its outstanding securities (other than short-term paper) are beneficially owned by not more than 100 persons.

Section 3(c)(7) of the Investment Company Act states, in part, that an issuer will not be an investment company if its outstanding securities are owned exclusively by persons who, at the time of acquisition of such securities, are “qualified purchasers” and it is not making and does not at that time propose to make a public offering of its securities. For purposes of this provision, the term “qualified purchaser” is defined by Section 2(a)(51) of the Investment Company Act.

8. Key terms of the venture capital fund?

a) Fund Strategy

The fund manager should define the investment strategy.

b) Traditional v. Tokenized Fund

In a traditional fund, investors’ limited partnership interests are illiquid, and investors are restricted from reselling shares in the fund.

In a tokenized fund, a fund manager could create blockchain tokens representing investors’ ownership interest in a fund. The benefit of tokenization is that all operations like token issuance, investor subscription, preferred return distributions, and secondary market trading are managed via blockchain smart contracts without any physical paperwork. These tokens would be treated as securities in the US, and so all regulatory requirements, including jurisdictional restrictions, KYC/AML, are automatically enforced via smart contracts.

c) Duration of the Fund

A typical period for a closed-ended VC is 5 to 7 years, after which the fund is terminated, and the proceeds realized from liquidating the fund’s assets are distributed to investors.

For example, all tokenized venture capital, biotech, pharma, and digital asset funds have been structured as closed-ended.

d) Decisions

The general partner manages all business and affairs of the fund and has a full control to make any decisions that the general partner deems reasonably necessary to require to accomplish the business and objectives of the fund.

Limited partners take silent seats in the fund and have no right or power to take part in the management of the fund.

e) Fees to Manager

It’s standard in the industry for the fund manager to receive the asset management fee. The asset management fee is typically set at 1 to 2% of the total funds under management, paid at the end of each calendar year month or quarterly.

d) Offering Timeline

The fund manager determines the offering timeline, which could last for as long as needed to reach the Maximum Offering Amount.

f) Maximum Offering

The maximum offering amount for a private VC fund could be as high as $100M without triggering the manager’s registration as an investment adviser under the Investment Advisers Act of 1940.

g) Preferred Return

The fund could offer a preferred annual return to investors. The return could be 6%, 8 or 12% which could vary depending on the fund’s strategy. The yearly preferred return is not a guarantee of payment and any distribution is contingent on the fund having sufficient available cash for distribution from its business.

h) Distribution Waterfall

Typically the fund’s distribution is done through a waterfall structure where investors first receive their invested capital back together with the accrued preferred return.

Then the investors and the general partner could split net capital proceeds 80-20. Depending on the fund’s strategy and asset class, there could be a 60-40 or 50-50 split, depending on what the parties negotiate. The general partners’ portion of the fund’s profit is called a carried interest which investor see this type of compensation as a performance bonus. The more profits the fund generates, the more carried interest the fund manager makes.

i)Side Letters

At some point while raising capital for a VC fund, a general partner will likely be asked by one or more potential investors to enter into a side letter. The use of side letters by VC funds is commonplace.

The general partner may enter into agreements with certain limited partners that will result in different terms of an investment in the fund than the terms applicable to other limited partners.

Side letters can also be used to grant special rights and privileges to important investors, which other investors will not receive, or accommodate last-minute investor requests closing without amending the entire stack of funds documents.

The General Partner typically does not have to notify the other Limited Partners of any such agreement or any of the rights and/or terms or provisions thereof, nor will the General Partner be required to offer such additional and/or different terms or rights to any other Limited Partner.

9. Determine the appropriate jurisdiction

Onshore funds: In the context of VC funds, onshore indicates a fund is located in the United States, such as a Delaware corporation. European locations for onshore funds would include the United Kingdom, Luxembourg, and Dublin. Compared to offshore alternatives, onshore locations have higher tax rates and more onerous and expensive regulatory rules.

Offshore funds: For U.S. investors, offshore might be a location like the Cayman Islands. European offshore jurisdictions might include Jersey or Guernsey, the largest of the Channel Islands. For example, in Jersey there are nearly 15,000 financial services professionals and nearly 900 different investment funds. These jurisdictions are generally faster, easier, and less expensive to work with than onshore alternatives.

Parallel funds: In some cases, where there are non-US investors, a parallel fund is created in jurisdictions outside of the one where the fund is located. These funds allow the GPs to pool their money into a separate fund that allows them to invest in the same fund on a no-load basis (i.e., without paying themselves a management fee or carried interest.)

Investors into parallel funds add capital into the same investment vehicles as the main fund and exit them simultaneously as well. They invest directly into each asset in parallel with the primary fund and in fixed proportions with their respective capital contributions.

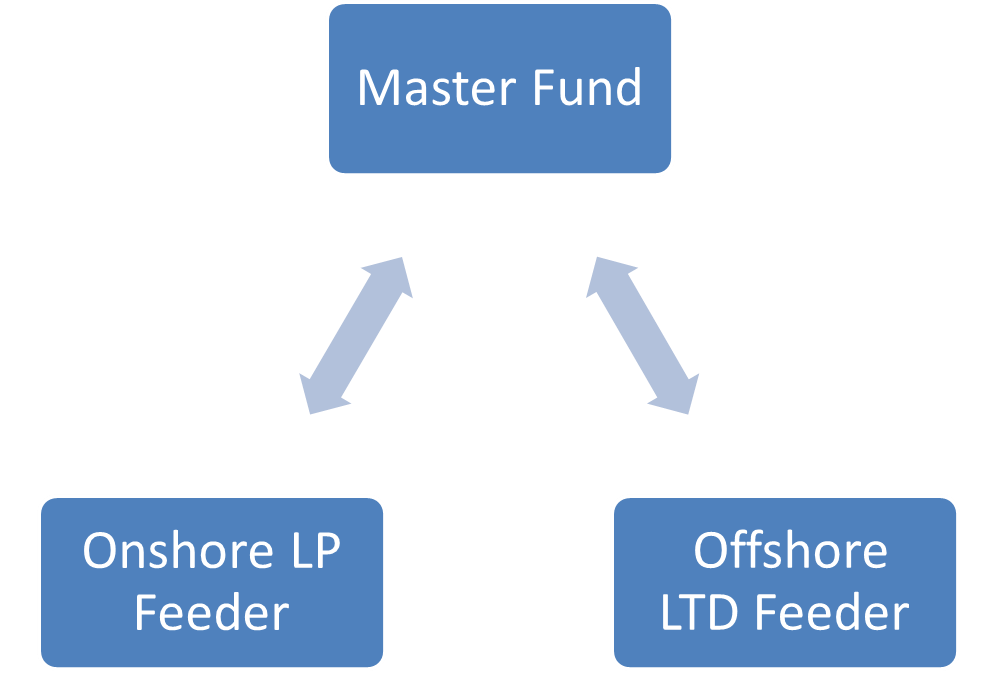

Master-feeder vehicles: This structure is commonly used to accrue funds raised from taxable and tax-exempt U.S. investors into one central vehicle (the master fund) in order to improve the economies of scale and enhance the critical mass of tradeable assets, which enhances operational efficiencies and reduces costs.

A master-feeder fund generally involves the use of a master corporation, located in a tax-neutral offshore jurisdiction) into which separate feeder funds invest. By electing certain tax remedies for U.S. taxable investors, these participants take advantage of investing into a U.S. limited partnership feeder fund. In order to avoid exposure to U.S. tax regulations, non-U.S. and U.S. tax-exempt investors participate via a separate offshore feeder company.

10. Issuance of Tokenized Fund Shares

In practice, deploying a security token takes the most time and effort. The pivotal issue is addressed at this stage, namely, ensuring that the digital security’s features and restrictions can be implemented and maintained throughout the security token’s life-cycle, including secondary trading.

While many platforms advertise their ability to issue legally compliant digital securities, you must conduct a detailed due diligence of the technical capabilities of a chosen tokenization platform for the primary issuance and future listing of a security token on a registered ATS, including:

Implementing Security Token’s Features

Before the issuance, fund managers will need to work with a tech team to make sure that all of the digital security’s features may be implemented using the protocol offered by the tokenization platform. Otherwise, if the legally structured qualities are not maintained from day one of the lifecycle, the security tokens may become useless and not tradeable.

Maintaining Resale Restrictions and Cap Tables

In addition to your designed features, all of the legally imposed requirements and limitations should be programmed into the security token and maintained throughout its lifecycle, including secondary trading.

Two of the principal requirements in the securities world, which all security token issuers should have learnt by this time, are maintaining the holding periods/resale restrictions and capital table.

Before listing, fund managers will have to demonstrate to ATSs that the applicable legal restrictions (or digital restrictive legends) are maintained.

Restrictions on a capital table vary depending on the applicable laws and regulations.

A lot of issuers are aware of the thresholds established by the Exchange Act, under which a U.S. issuer with total assets above $10 million and more than 2,000 holders of record of a class of equity securities (or 500 holders of record who are not accredited investors) must register those equity securities with the SEC

ATS Compatibility

Finally, the minted tokens must be compatible with the chosen regulated ATSs to be listed and tradeable. This challenge should be addressed beforehand as different tokenization platforms and ATSs have different standards and protocols – some are still being restructured or developed.

The employed tokenization platform will need to establish contacts with the ATS of your choice before the primary issuance to ensure that the issuer’s and platform’s configurations of digital securities match and the pre-listing procedures required by the ATS are adhered to.

Some of the ATS platforms offer all-in-one tokenization, marketing and listing services, which may simplify your task but still require an in-depth due diligence on the possible issues outlined above.

If the offering is poorly structured or documented, the digital security’s features are unenforceable for secondary trading, or if the security tokens are incompatible with the selected ATS, blockchain projects may be tempted by a seemingly simple technical solution – recalling the flawed security

tokens and replacing them with the new ones.

However, this may not be possible or may be costly and complicated from the legal standpoint, as one cannot always simply recall the issued securities, albeit in the form of digital tokens.

Resources:

- Introduction to Private Equity Funds

- Private Equity Funds – Formation and Operation

- Closed-End Fund Formation

- Private Equity Demystified – Explanatory Guide

- How to Start a Hedge Fund

- SEC’s Analysis of the Market for Unregistered Securities Offerings

- Tax Treatment of Partnership Funds and Mergers of Investment Companies

- Hedge Fund Basics – IRS Guide

- Opportunities in Private Equity

- Private Equity in the Developing World: Determinants of Transaction Structures

- Hedge Fund Fully Managed by Artificial Intelligence

- Sample Limited Partnership Agreement of the Fund

- Private Equity, Venture Capital and Hedge Funds

- Hedge Fund Basics – IRS

- Supporting Innovation Through SEC’s Mission to Facilitate Capital Formation

- Information and Observation on State Venture Capital Programs

- Funds of Funds Arrangments

- Framework for Investor Analysis of Hedge Fund Governance

- Implications of the Growth of Hedge Funds – SEC.gov